The Dilemma: Hard Choices in Front of Us

“As people get richer, diets tend to diversify and meat consumption rises. The average American ate 53 pounds of beef—the most carbon intensive meat—according to USDA. Growing middle classes in developing countries from China to South Africa are eating more meat than ever. Cars are the biggest source of per-capita emissions in the U.S. and the second biggest in Europe. Changing that, and much else, requires changing social norms. As more of the global poor become able to afford sport-utility vehicles, air travel, meat and other elements of the high-carbon lifestyle, political impediments to reducing these new emissions will likely rise.

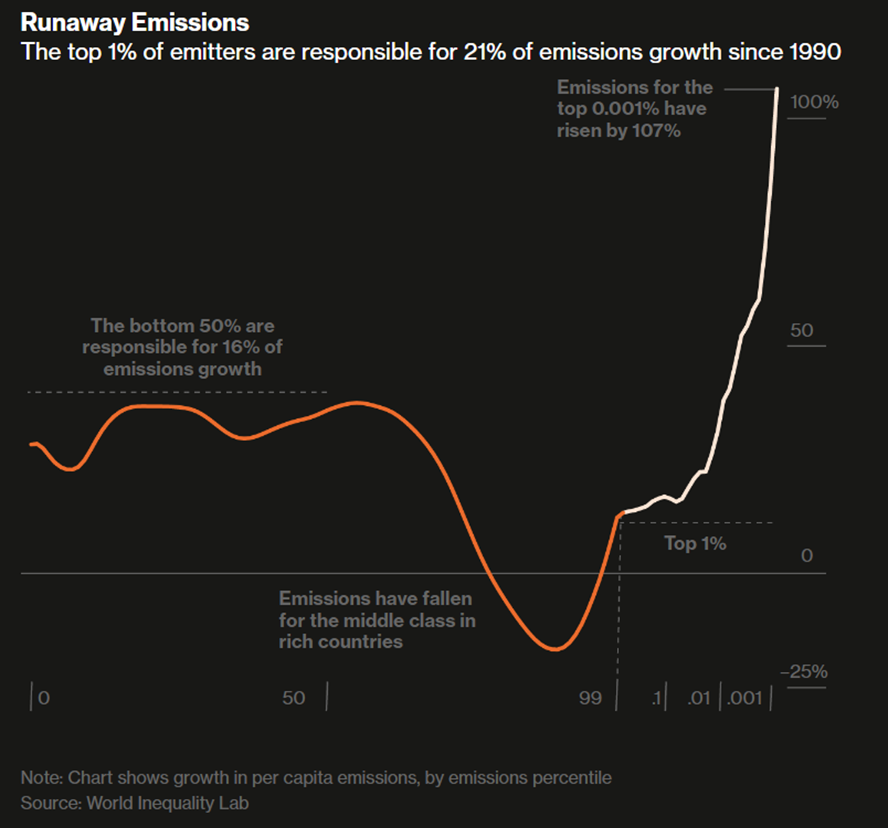

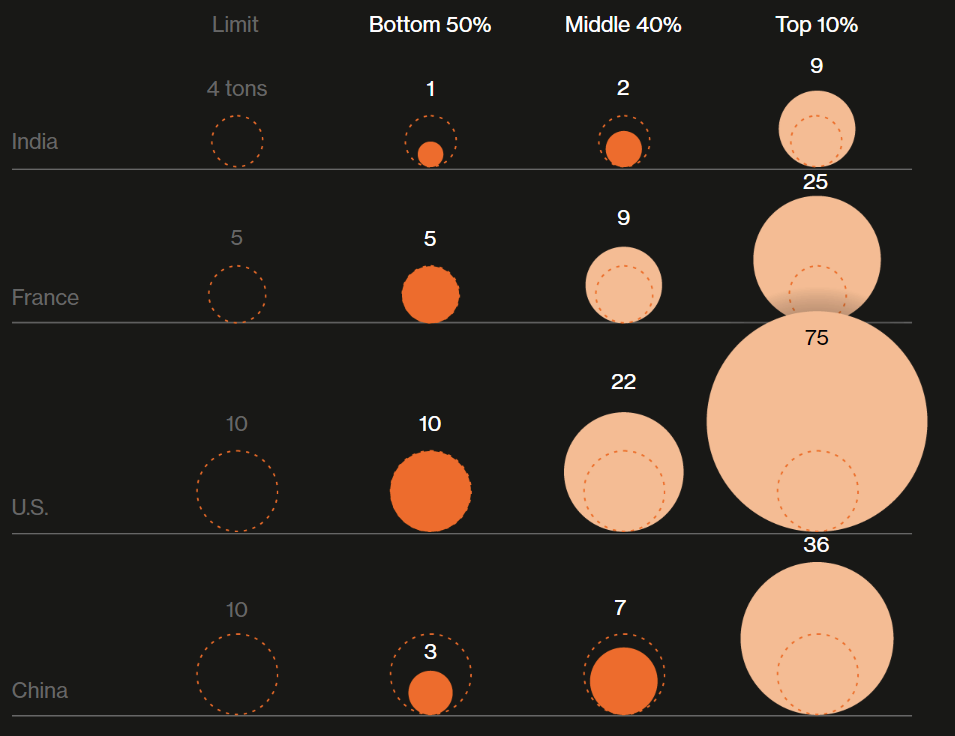

Far higher up the income distribution, the emissions increase exponentially. A recent analysis of the lifestyles of 20 billionaires found that each produced an average of over 8,000 tons of carbon dioxide: 3,500 times their fair share in a world committed to no more than 1.5C of heating. The major causes are their jets and yachts. A superyacht alone, kept on permanent standby, as some billionaires’ boats are, generates around 7,000 tons of CO2 a year. An 11-minute ride to space, like the one taken by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, is responsible for more carbon per passenger than the lifetime emissions of any one of the world’s poorest billion people. A short private jet flight generates as much carbon dioxide as an average person in the European Union emits all year.

As consumers and investors, the choices of the wealthy can have outsize impact, especially on transport and housing. Just 1% of the world’s population is responsible for half the aviation emissions. The top 0.001%—whose responsibility is so great that their decisions can have the same climate impact as nationwide policy interventions. Together, the top 10% of emitters generate more than four times as much carbon as the global average.”

Unless there are wealth taxes on the rich to drive environmental measures, it is difficult to motivate and sustain a lifestyle change among the rich for the sake of the planet. The very rich claim to be wealth creators but will continue to remain ecological detractors.

Based on various sources: World inequality lab, Nature, Bloomberg, Guardian

There are strong institutional, cultural and individual barriers to adopting lifestyle changes. Knowledge about climate change by itself is insufficient to catalyze change and the strong barrier for lifestyle changes outweigh motivation.

Individual willingness:

People's own unwillingness to change. Forming new habits is perceived as hard work. Example, Difficult to imagine a life without meat and dairy. There is an ingrained skepticism that vegetarian food is not a proper meal

Habits:

A busy life means it is easy to continue with bad habits, despite “knowing better.” Habits and routine can trump the ability for information or education to make much of a difference, in the absence of stronger incentives. Lifestyle change hasn't been high on the list of priorities.

Structural barriers:

Living location: Where you live determines your access to institutional and public goods. Most people are bound by the location where they live due to job opportunities and social ties. Example: Existing public transport solutions that are not a good substitute for cars due to poor coverage for solving daily logistics.

Cost as a barrier for change

Example: Changing to heat pump is nice, but it costs money. Investment costs of more efficient sources of heating is an important barrier to efficiency upgrades in existing homes

Convenience:

People will make decisions based on whether it’s an easy choice to make

Societal Norms and Values:

Consumption is a major component of shared societal and cultural norms and can contribute to a sense of belonging. Even knowledgeable and willing individuals may not reduce meat intake or adopt other high impact actions if cultural norms or structural barriers act as obstacles

Source: IZA DP No. 14518: Fighting Climate Change: The Role of Norms, Preferences, and Moral Values, IZA.org

A key factor that can shape perceptions of climate change is people's personal experience of extreme weather events and/or local weather anomalies such as temperature fluctuations. Such experiences provide an opportunity for individuals to witness the otherwise abstract effects of climate change and as such make the risk more tangible and familiar. They can reduce perceived psychological distance of climate change.

Personal experience with severe storms and associated floods, hurricanes, heatwaves, and droughts can influence climate change beliefs and concern, at least temporarily. Experiences with such events may also increase perceived risk, increase environmental concern and promote action.

However, in some individuals the perceived threat from climate change does not trigger a willingness to take action. This is because intense negative effect can induce fear in some individuals, and as a result lead to avoidant behaviors and denial. Pre-existing values and beliefs of individuals shape how they experience changes in environmental conditions. People interpret and process information in a biased manner to maintain their prior beliefs.

The influence of event recency, personal and financial damages, local warming, and psychological and social contexts; all of which may shape how individuals perceive and interact with weather-related experiences.

Source: Climate change and human behaviour, 2022, Nature, The Role of Personal Experience and Prior Beliefs in Shaping Climate Change Perceptions, Frontiers.org

Truly sustainable development would mean providing decent living standards for everyone at much lower, sustainable levels of energy and resource use. But, in our current economic system, all countries that achieve decent living standards use much more energy than what can be sustained if we are to avert dangerous climate breakdown.

Policies that could enable countries to use less energy whilst providing the whole population with 'decent living standards' satisfy fundamental human needs - food, water, sanitation, health, education, and livelihoods. Policies aimed to scale back resource extraction, prioritize public services, basic infrastructures and fair income distributions is critical to raise the living standards without further warming. To reduce existing income disparities, governments could raise minimum wages, provide a Universal Basic Income, and introduce a maximum income level - higher taxes on high incomes, and lower taxes on low incomes.

With these policies in place, rich countries could slash their energy use and emissions whilst maintaining or even improving living standards; and less affluent countries could achieve decent living standards and end material poverty without needing vast amounts of energy.

Achieving this ultimately requires a broader, more fundamental transformation of our growth-dependent economic system. Economic growth beyond moderate levels of affluence is detrimental for aspirations of sustainable development. Decent living standards require neither perpetual economic growth nor high levels of affluence. Fundamental changes in economic and social priorities are required to resolve the dilemma of sustainable development.

Source: Socio-economic conditions for satisfying human needs at low energy use: An international analysis of social provisioning. Global Environmental Change, 2021, University of Leeds

A commonly quoted axiom summarizes the difficulty of such a profound shift in economic models, “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism” explains the difficulty of pivoting to new economic models.

But, a lot of these alternative models are being discussed by economists as fears grow over climate change due to the pitfalls of the current economic models in depleting earth’s finite resources.

Eco Capitalism: a.k.a Green capitalism is the idea of retaining the economic growth using free market system to resolve environmental problems.

Doughnut economics is based on a Floor and Ceiling Framework. Sustainable lifestyles are situated between an upper limit of permissible use (“Environmental ceiling”) and a lower limit of necessary use of environmental resources (“Social foundation”). Some policies that promote the downshifting of consumption and production: Carbon Tax, Cap and Trade, Investment in green energy companies, taxation/maximum income ceiling, and a guaranteed basic income floor.

De-Growth: Degrowth broadly means shrinking rather than growing economies, so we use less of the world’s energy and resources and put wellbeing ahead of profit. Detractors of degrowth say economic growth has given the world everything from cancer treatments to indoor plumbing. Supporters argue that degrowth doesn’t mean “living in caves with candles” – but just living a bit more simply. Global interdependence makes it difficult for a country to undertake a degrowth transition on its own. Doing so would entail substantial penalties from capital flight, bank and currency collapses, asset devaluations, collapse of public and security institutions, and political isolation. This would undermine the ability of a nation to pursue a quiet contraction on its own. Likewise, if a single country or block of countries were to successfully downscale their economies, a global reduction of resource prices would likely follow, producing a rebound in consumption elsewhere. In a sense, then, escaping growth is a global collective action problem. To be successful, the transition to degrowth must be global.

Eco-socialism usually focus more on rationing, planning of investments and employment, price controls and public ownership of at least the most central means of production to plan their downscaling in a socially sustainable way

Whether economic growth can be sustained while tackling climate change and staying within wider environmental limits is an area of ongoing debate. Different perspectives range from a view that economic growth is not bounded by environmental limitations to one that suggests sustained economic growth is simply not compatible with environmental limitations.

Since the Industrial Revolution, economic growth has generally been tied to increasing greenhouse gas emissions. A switch from fossil fuel-based to low-carbon energy sources can help sustain the same or even higher levels of production while reducing emissions, thereby enabling the decoupling of growth from emissions. General technological development can also help decouple growth from emissions by reducing input energy or other material required for production in the first place. The ongoing digital transformation of the economy through the development of information and communication technology (ICT) may also have a positive impact on decoupling.

Over the past few decades, many high-income countries (see UK, Germany and US) have shown signs of decoupling their economic growth from emissions, even when taking offshored production into account. The reasons for this have included – to varying degrees in different countries – the transition away from coal and uptake of low-carbon energy, explicit climate change policies, and also a shift away from manufacturing to less carbon-intensive, service-based industries.

If low-carbon energy becomes significantly cheaper than fossil fuels, the emissions intensity of GDP could be lowered to the degree required for absolute decoupling of emissions from economic output. Achieving absolute decoupling of emissions from economic output would be challenging and require major investment into low-carbon energy and universal acceptance in a short window of time.

So, In theory, advances in environmental efficiency can help to “decouple” economic growth from resource use and pollution. But the outcomes remain elusive in the real world since the global temperatures are still rising.

Source: London school of economics “Can we have economic growth and tackle climate change at the same time?”

Green growth has emerged as the dominant narrative for tackling climate change. It says that sustainability can be achieved through efficiency, technology and market-led environmental action. Green growth tests the possibility of both growing the economy and protecting the planet. However, there is skepticism on its effectiveness. Green consumption is still consumption. The very act of green consumption still fuels the extraction and use of natural resources, pollution and environmental degradation. Stuff requires more stuff to produce – this is often overlooked when we buy re-useable cups, eco-appliances and “sustainable” clothing. Any positive impacts of green consumption can also easily be undone through people feeling they have a moral license to indulge elsewhere. Although market mechanisms can guide businesses towards sustainable behavior, stringent laws and regulation are necessary to bring their growth in line with environmental limits.

Based on various sources: UN.org, McKinsey, IMF

In a circular economy, things are made and consumed in a way that minimizes our use of the world’s resources, cuts waste and reduces carbon emissions. Products are kept in use for as long as possible, through repairing, recycling and redesign – so they can be used again and again.

At the end of a product’s life, the materials used to make it are kept in the economy and reused wherever possible. The circular economy is an alternative to traditional linear economies, where we take resources, make things, consume them and throw them away. This way of living uses up finite raw materials and produces vast quantities of waste.

In 2022, the global economy was only 8.6% circular, leaving a massive circularity gap. By doubling global circularity in the next 10 years, global greenhouse gas emissions could be reduced by 39% and shrink the total material footprint by 28% by 2032, compared to current levels. Two-thirds of all countries (127 of 197) who signed the Paris Agreement have not yet included the circular economy in their climate commitments. Countries that consume a vast volume of resources and produce large amounts of waste and emissions, such as the G20 group, must take greater responsibility for their impact and incorporate stronger circular targets and strategies into their climate commitments.

Source: weforum.org, WRI.org

Climate justice calls for top GHG emitting countries, along with multinational corporations that have become wealthy through polluting industries, to pay their “climate debt” to the rest of the world. Countries that became wealthy through unrestricted carbon emissions have the greatest responsibility to not only stop warming the planet, but also to help other countries adapt to climate change and develop economically with nonpolluting technologies.

A climate justice perspective also brings attention to inequalities within countries. Within high and low income countries, wealthier people are more likely to enjoy energy-intensive homes, private cars, leisure travel, and other comforts that both exacerbate climate change and buffer them from impacts like extreme heat. Climate change also worsens pre-existing social inequalities stemming from structural racism, socioeconomic marginalization, and other forms of social exclusion.

An example of Climate Justice - a carbon tax that makes it expensive to emit greenhouse gases should be structured in a way that protects low-income people who are already struggling to pay for gasoline, home heating and cooling, and other basic energy needs.

Global South nations, Black, Indigenous, and other people of the global majority and women—who have been historically excluded from decision making—have led the push for climate justice, arguing that climate change endangers their health and livelihoods. In recent years, younger people have also been leading the call for just climate action, observing that they will bear the heaviest burden from the climate change that past generations have contributed to, and demanding immediate action from those in positions of power.

Source: MIT climate portal

Climate reparations are a mechanism to pay developing countries for losses and damages they’ve suffered from climate change—a problem they did little to create. Wealthy nations such as the United States have opposed the idea for years. But its advocates have stayed persistent as climate impacts have grown more severe. A historic loss and damage fund was established at COP 27. Representatives from 24 countries will work together in 2023 to decide what form the fund should take, which countries should contribute, and where and how the money should be distributed.

The fund accounts for the economic toll of climate-fueled disasters, such as floods, wildfires, hurricanes and slow-onset climate impacts, such as sea-level rise, that can produce irreversible damage over time. Taken together, these are climate change impacts that countries can’t defend against, either because the risks are unavoidable or because countries don’t have the money to pay for protection. Because of this and other climate impacts, a country can lose homes, farmland and jobs—damaging economic growth. Governments can take steps to adapt, but when impacts exceed adaptation, it’s considered loss and damage.

Payment for climate reparations differs from funding that goes toward mitigation or adaptation—two established pillars of climate action. Mitigation refers to efforts to cut the greenhouse gas emissions that are warming the planet by, for example, switching from coal-fired power to solar or wind. Adaptation helps protect against climate-related damages. Loss and damage is considered a third pillar, and in many ways, it exists because actions to reduce emissions and support adaptation have fallen short. Total loss and damages in developing countries could reach between $290 billion and $580 billion by 2030.

In comparison, the U.N.’s Green Climate Fund was created to help developing nations reduce emissions and build resilience to climate impacts. The 2022 Adaptation Gap Report indicates that international adaptation finance flows to developing countries are five to ten times below estimated needs, and will need over US$300 billion per year by 2030.

Source: 5 things to know about climate repatriations, Scientific American and

what-you-need-know-about-cop27-loss-and-damage-fund, UNEP

A global mass mobilization that employs either nonviolent or more confrontational tactics has the potential to motivate the type of social transformation needed. Nonviolent conflict has been found to be successful in bringing about such large-scale social transformations if a critical mass of 3.5% or more of the population participates in the activism.

As the sense of urgency grows and more countries experience climate-related disasters — such as the extreme flooding in Pakistan and drought in Somalia — we might see more confrontational activism.

Social change research suggests radical actions have historically been effective in raising awareness – particularly useful in the early phases of a movement – because the media are more likely to cover actions when they are sensational or violate social norms. On the one hand, radical actions can bring greater attention to a cause, but they can simultaneously reduce support for that cause. A lot of climate activists are resorting to these more radical tactics, because time is running out.

Source: Yale.edu, Guardian

Achieving a rapid global decarbonization to stabilize the climate critically depends on activating contagious and fast-spreading processes of social and technological change within the next few years. A set of social interventions are required to overcome the rigidities inherent in political and economic decision making. These interventions will create social tipping points that can activate contagious processes of rapidly spreading technologies, behaviors, social norms, and structural reorganization.

They include removing fossil-fuel subsidies and incentivizing decentralized energy generation, building carbon-neutral cities, divesting from assets linked to fossil fuels, revealing the moral implications of fossil fuels, strengthening climate education and engagement, and disclosing greenhouse gas emissions information.

Source: Social tipping dynamics for stabilizing Earth’s climate by 2050, PNAS

Biodiversity and ecosystems play an essential role for climate regulation. Peatlands, wetlands, soil, forests and oceans absorb and store carbon, and helps to protect us from climate change. Ecosystems already provide natural carbon traps at very little cost. Land and and marine ecosystems absorb roughly half of the CO2 emissions humanity generates. Maintaining existing natural carbon reservoirs worldwide is essential if carbon capture and storage is to make a major contribution to climate mitigation.

Deep ocean stores large amount of carbon. Coastal ecosystems like wetlands, mangroves, coral reefs, oyster reefs, and barrier beaches all provide natural shoreline protection from storms and flooding and create nurseries for fishing.

Protecting groundwater recharge zones, or restoring flood plains, secure water resources so that rural communities can cope with drought.

Some low cost ways to enhance natural protection are as follows: 1) preservation and restoration of degraded land, forests, peatlands, organic soils, wetlands 2) reduction in conversion of pastureland, less slash and burn practices, and improved grassland management.

Conservation of biodiversity is often misinterpreted as a marginal issue concerning merely the protection

of endangered species, and the crucial role of nature for combating climate change is often overlooked.

Source: UNEP, Europa

The answer is complicated. While solar panels are an environmentally friendly energy solution, the materials and manufacturing process used to create them do have a decent-sized carbon footprint, as they involve mining, melting and cooling to be used. Photovoltaic panel production involves carbon emissions, toxic waste, unsustainable mining practices and habitat loss. Solar panel facilities also require a lot of energy to keep up and running, and unfortunately, a lot of the energy used for melting down silicon comes from coal burning, for which pollution emissions are very high. T here’s also a great need for water for the cooling process, which can be an environmental strain in more arid areas where water isn’t as available.

Battery manufacturing for Electric vehicles also have a huge upfront carbon footprint. Most lithium is extracted from hard rock mines or underground brine reservoirs, and much of the energy used to extract and process it comes from CO2-emitting fossil fuels. Particularly in hard rock mining, for every ton of mined lithium, 15 tons of CO2 are emitted into the air.

Battery materials come with other costs, too. Mining raw materials like lithium, cobalt, and nickel is labor-intensive, requires chemicals and enormous amounts of water—frequently from areas where water is scarce—and can leave contaminants and toxic waste behind. 60% of the world’s cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where questions about human rights violations such as child labor continue to arise.

However, both solar and EVs are relatively clean over the life vs. the fossil-based alternatives.

Source: MIT climate portal, WRI

Given the scale of climate change, and the fact that it will affect many areas of life, adaptation and resilience needs to take place on both large and small scale. Our economies and societies as a whole need to become more resilient to climate impacts. This will require large-scale efforts, many of which will be orchestrated by governments.

Roads and bridges may need to be built or adapted to withstand higher temperatures and more powerful storms. Some cities on coastlines may have to establish systems to prevent flooding in streets and underground transport. Mountainous regions may have to find ways to limit landslides and overflow from melting glaciers. Some communities may even need to move to new locations because it will be too difficult to adapt. This is already happening in some island countries facing rising seas.

Adaptation measures will be expensive, but protecting people now saves more lives and reduces risks moving forward. It makes financial sense too because the longer we wait, the more the costs will escalate. Universal access to early warning systems can deliver benefits up to 10 times the initial cost. And if more farms installed solar-powered irrigation, used new crop varieties, had access to weather alert systems and took other adaptive measures, the world would avoid a drop-off in global agricultural yields of up to 30 per cent by 2050.

For people and society, adaptation to climate change means adjusting our behaviour (e.g. where we choose to live; the way we plan our cities and settlements) and adapting our infrastructure (e.g. greening of urban areas for water storage) to deal with the changing climate - today and in the future. Individuals can take some simple measures. You can plant or preserve trees around your home, for instance, to keep temperatures cooler inside. Clearing brush might reduce fire hazards. If you own a business, start thinking about and planning around possible climate risks, such as hot days that prevent workers from doing outside tasks.

Everyone should be aware of the possibly greater potential for natural disasters where they live and what resources they have in case these happen. That might mean purchasing insurance in advance, or knowing where you can get disaster information and relief during a crisis.

Estimated adaptation costs in developing countries could reach $300 billion every year by 2030. Right now, only 21 per cent of climate finance provided by wealthier countries to assist developing nations goes towards adaptation and resilience, about $16.8 billion a year.

Source: UN.org, IPCC.ch

“Think about the world as a whole system — where atmosphere, ocean, land, and life collide with spectacular diversity. Astronauts have experienced a cognitive shift when viewing earth from the space – called as ‘Overview Effect’- A state of awe with self-transcendent qualities that changes their self-concept and value system. They experience an increased sense of connection to other people and the Earth as a whole. The earth is the safest place that we know and our safety depends on being within its planetary boundaries. Crossing a planetary boundary comes at the risk of abrupt environmental change.

Whether we’re causing climate change, degrading ecosystems, or using up our natural resources, environmental problems begin when we ignore the limits of our planet. All imagined realities such as the greatest nation, richest person, most powerful and largest company becomes irrelevant when the planet is at the risk of a collapse.

Our greatest challenge is to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet - Providing life's essentials (food, housing, healthcare, education, water, energy etc.), while not overshooting the Earth's life-supporting systems, on which we fundamentally depend (stable climate, fertile soils, Ocean, Air).

And to do that, all 8 billion people in the planet may need to experience an ‘Overview Effect’.

Source: Planetary Perspective, By Dr. Jonathan Foley and Dougnut economics by Kate Raworth